Benzene

Benzene Profile

INDUSTRIAL CHEMICALS – KNOWN CARCINOGEN (IARC 1)

Contents

Benzene Profile

QUICK SUMMARY

- A naturally occurring substance in crude oil; also produced from the incomplete combustion of organic materials

- Associated cancer: Acute non-lymphocytic leukemia

- Most important route of exposure: Inhalation; skin contact

- Uses: As a raw material to produce other chemicals such as styrene and acetone, as well as synthetic fibres

- Occupational exposures: Approx. 360,000 Canadians are exposed at work, often via motor vehicle exhaust

- Environmental exposures: Primarily in indoor air via a number of sources including glues, paints, and combustion sources (ex. fireplaces)

- Fast fact: Benzene is considered a ‘non-threshold toxicant’, where adverse health effects may occur at any exposure level.

General Information

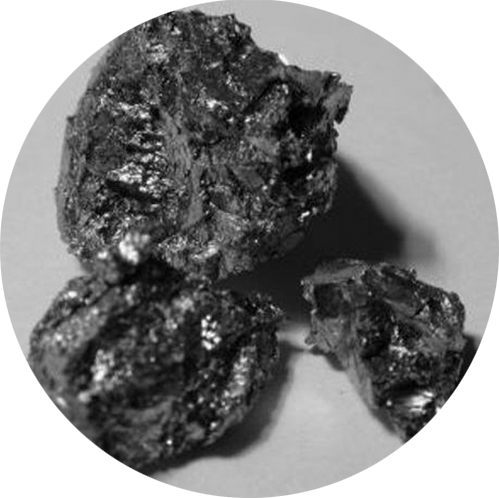

Benzene, an aromatic hydrocarbon, is a clear, usually colourless liquid with a gasoline-like odour.[1] Benzene occurs naturally as a constituent of crude oil. It has been synthesized from coal since 1849 and from petroleum sources since 1941.[1] Trace amounts of benzene are produced from the incomplete combustion of organic materials.[2] Benzene may also be referred to as benzol or coal naphtha.[3] There are numerous other synonyms and product names; see the Hazardous Substances Data Bank (HSDB) for more information.[3]

Benzene has been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as Group 1, carcinogenic to humans.[1,4] The 2017 review by IARC reaffirmed this classification, citing sufficient evidence of human carcinogenicity for acute non-lymphocytic leukemia/acute myeloid leukemia and limited evidence of carcinogenicity for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Positive associations were also observed for chronic myeloid leukemia and lung cancer.[4]

Although the hematopoietic system is the main target for benzene toxicity, the immune, lymph and nervous systems are also adversely affected by exposure.[5] Short-term exposure can cause drowsiness, headaches, and unconsciousness. The effects of long-term exposure include anaemia, neuropathies, and memory loss.[5] Benzene is also a skin irritant.[5]

Regulations and Guidelines

Occupational exposure limits (OEL) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]

| Canadian Jurisdictions | OEL (ppm) |

|---|---|

| Canada Labour Code | 0.5 [sk] 2.5 [stel] |

| AB, BC, MB, NB, NS, NL, ON, PE | 0.5 [sk] 2.5 [stel] |

| QC | 1 [em] 5 [stel] |

| YT | 10 [c] |

| SK, NU, NT | ALARA (no limit listed) |

| Other Jurisdiction | OEL (ppm) |

| ACGIH 2020 TLV | 0.5 [sk] 2.5 [stel] |

ppm = parts per million

sk = easily absorbed through the skin

stel = short term exposure limit (15 min. maximum)

em = exposure must be reduced to the minimum

c = ceiling (not to be exceeded at any time)

ALARA = as low as reasonably achievable

ACGIH = American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists

TLV = threshold limit value

Canadian environmental guidelines and standards*

| Jurisdiction | Limit | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Drinking Water Guidelines (Canada, BC, MB) and Standards (SK) | 0.005 mg/L | 2009-2020 [21,22,23,24] |

| Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards | 0.001 mg/L | 2016[25] |

| Quebec’s Drinking Water Standards | MAC: 0.5 µg/L | 2014[26] |

| Government of Canada’s residential indoor air quality guidelines | ALARA | 2013[27] |

| Alberta Ambient Air Quality Objectives | 1 hour: 30 µg/m3 Annual: 3 µg/m3 | 2017[28] |

| Ontario Ambient Air Quality Criteria | 24 hour: 2.3 µg/m3 Annual: 0.45 µg/m3 | 2016[29] |

| Ontario’s Air Pollution – Local Air Quality regulation standards | Annual: 0.45 µg/m3; Prohibited discharge into the air if the concentration of benzene exceeds the standard | 2020[30] |

| Quebec’s Clean Air Regulation | 24 hour limit: 10 µg/m3; Prohibited discharge into the air if the concentration of benzene exceeds the standard | 2011[31] |

| BC’s Contaminated Sites Regulation, BC Reg 375/96 | Sets soil standards for the protection of human health: Agricultural and low density residential sites: 150 μg/g Urban park and high density residential sites: 350 μg/g Commercial sites: 1,000 μg/g Industrial sites: 6,500 μg/g

Drinking water: 5 μg/L Sets vapour standards (for vapours derived from soil, sediment, or water) for the protection of human health: | 2017[32] |

| Cosmetic Hotlist | Not Permitted | 2011[33] |

*Standards are legislated and legally enforceable, while guidelines (including Ontario ambient air quality criteria) describe concentrations of contaminants in the environment (e.g. air, water) that are protective against adverse health, environmental, or aesthetic (e.g. odour) effects

MAC = maximum allowable concentration

ALARA = as low as reasonable achievable

Canadian agencies/organizations

| Agency | Designation/Position | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Health Canada | DSL – low priority substance (already risk managed) | 2006[34] |

| CEPA | Schedule 1, paragraph ‘c’ | 2011[35] |

| National Classification System for Contaminated Sites | Rank = “High hazard”, potential human carcinogen | 2008[36] |

| Benzene in Gasoline Regulations | 1.0% max. benzene (by volume) in supplied gasoline (Exceptions: aircraft use, vehicle competitions, scientific research) | 2011[37] |

| Environment Canada’s National Pollutant Release Inventory | Reportable to NPRI if released at quantities greater than 1 tonne of 10-tonne total VOC air release or if manufactured, processed, or otherwise used at quantities greater than 10 tonnes | 2016[38] |

DSL = domestic substance list

CEPA = Canadian Environmental Protection Act

Benzene was not included in other Canadian government guidelines, standards, or chemical listings reviewed.

Main Uses

Benzene is used primarily as a raw material to produce chemicals including: ethylbenzene, for styrene; cumene, for phenol and acetone; and cyclohexane, for nylon and synthetic fibres.[1,5]

Benzene was formerly added to gasoline as an octane enhancer and anti-knock agent (along with toluene and xylene).[2] Benzene is generally no longer used as a gasoline additive in Canada, but it does occur naturally in crude oil and gasoline.[39] Benzene has also been used to manufacture rubbers, lubricants, dyes, detergents, drugs, and pesticides.[5]

Environmental Exposures Overview

CAREX Canada estimates that the primary source of environmental exposure to benzene is indoor air. Benzene is emitted by a number of indoor sources, including glues, paints, furniture wax, and some detergents.[42] Combustion sources such as fireplaces, gas furnaces, cigarette smoke, and vehicles in attached garages may also contribute to indoor concentrations of benzene.[43] Having an attached garage can lead to increased exposure since benzene can more readily enter the house.[44] For example, in Canada, benzene levels are three times higher in homes with attached garages compared to those with detached or no garages. The presence of benzene is attributable to engine exhaust, as well as to the evaporation of benzene from gasoline.[44] A recent survey of homes across Canada found indoor concentrations of benzene ranging from 0.10 to 15.19 µg/m3, with average concentrations of 1.93 µg/m3.[45] CAREX Canada’s environmental estimates indicate that benzene levels in indoor and outdoor air may be sources of elevated cancer risk (high data quality).

Outdoor concentrations of benzene are generally lower than indoor concentrations.[46] Major sources of benzene in outdoor air include vehicle combustion of gasoline and diesel fuels, residential fuel combustion, iron and steel production, chemical manufacturing, as well as petroleum and coal products manufacturing.[2,42] Natural sources of benzene in the environment include forest fires, volcanos, petroleum seepage, and emissions from vegetation.[42]

Ambient air benzene levels in different locations in Canada have been monitored since 1989 by the National Air Pollution Surveillance (NAPS) network. A 2012 NAPS update indicated that the concentrations of benzene at 18 urban sites decreased by 74% between 1994 and 2009.[47]

Low levels of benzene are found in some soft drinks and a number of other foods and beverages.[48,49] Benzene contamination in soils and groundwater may also arise from oil and gas spills, underground storage tank leaks, and seepage from waste disposal sites.[3] CAREX Canada’s environmental estimates indicate that benzene levels in food and beverages may be sources of elevated cancer risk (very low data quality), although not in drinking water (moderate data quality).

Searches of Environment Canada’s National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) and the US Consumer Product Information Database yielded the following results on current potential for exposure to benzene in Canada:

NPRI and US Consumer Product Information Database

| NPRI 2015[50] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Substance name: ‘Benzene’ | ||

| Category | Quantity | Industry |

| Released into Environment | 736 t | Oil and gas extraction, basic chemical manufacturing, iron and steel mills and ferro-alloy manufacturing, petroleum and coal product manufacturing (234 facilities) |

| Disposed of | 1,065 t | |

| Sent to off-site recycling | 1,055 t | |

| US Consumer Products 2016[51] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Search Term | # Products | Product Type |

| ‘Benzene’ | 17 | adhesives (3), interior paints (2), wood finish (1), adhesive remover (1), pet care lotion (1), sealant (1), auto part cleaner/degreaser (5), motor oil (3) |

t = tonne

For more information, see the environmental exposure estimate for benzene.

Occupational Exposures Overview

The most important route of occupational exposure to benzene is inhalation, but dermal exposure can also occur.[1,5]

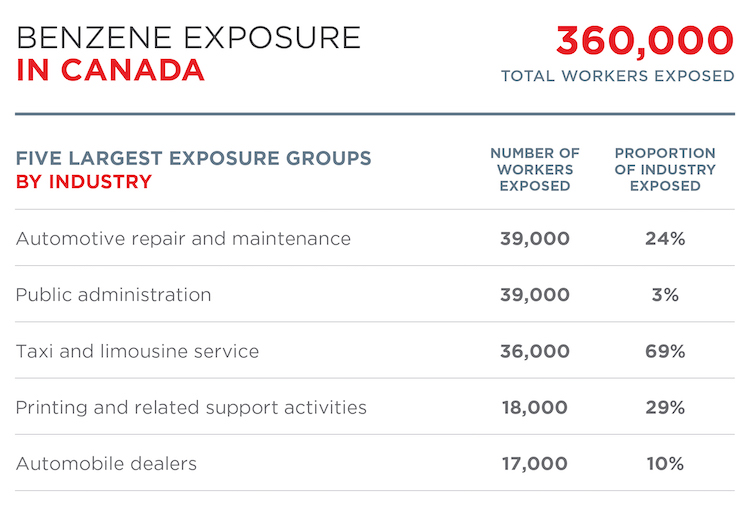

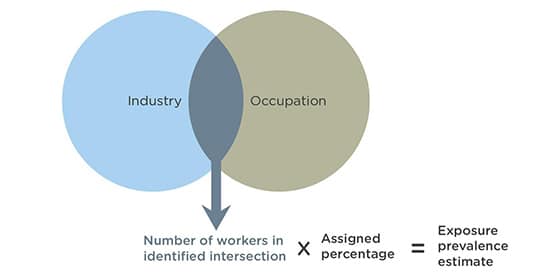

CAREX Canada estimates that approximately 360,000 Canadian workers are exposed to benzene; most exposures occur in the low exposure category. Many workers are exposed to benzene via inhalation of motor vehicle exhaust.

Industries where the largest numbers of workers are exposed include automotive repair and maintenance, public administration (where firefighters are included), and taxi and limo service. According to the US Department of Labour, benzene exposure is also likely during petrochemical production, petroleum refining, coke and coal chemical manufacturing, tire manufacturing, and storage or transport of benzene and petroleum products containing benzene.[52]

Occupations at risk of benzene exposure include automotive service technicians and mechanics, delivery and courier drivers, taxi and limousine drivers, and firefighters. Other occupations such as steel workers, printers, rubber workers, shoemakers, laboratory technicians, and gas station employees were also identified as exposed.[52]

According to the Burden of Occupational Cancer in Canada project, occupational exposure to benzene leads to approximately 20 leukemia cancers, and less than 5 possible multiple myeloma cancers each year in Canada, based on past exposures (1961-2001).[53,54] This amounts to 0.5% of all leukemia and 0.2% of all multiple myeloma cancers diagnosed annually. Most benzene-related cancers occur among workers in the manufacturing, transportation and warehousing, and trade sectors.[54]

For more information, see the occupational exposure estimate for benzene.

Sources

Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Ilya Plekhanov

Subscribe to our newsletters

The CAREX Canada team offers two regular newsletters: the biannual e-Bulletin summarizing information on upcoming webinars, new publications, and updates to estimates and tools; and the monthly Carcinogens in the News, a digest of media articles, government reports, and academic literature related to the carcinogens we’ve classified as important for surveillance in Canada. Sign up for one or both of these newsletters below.

CAREX Canada

School of Population and Public Health

University of British Columbia

Vancouver Campus

370A - 2206 East Mall

Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3

CANADA

As a national organization, our work extends across borders into many Indigenous lands throughout Canada. We gratefully acknowledge that our host institution, the University of British Columbia Point Grey campus, is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people.