Asbestos Environmental Exposures

Asbestos Environmental Exposures

Overview

In the environment, the primary route of exposure is by inhaling air contaminated with asbestos. People may be exposed to higher-than-average levels of asbestos in air if they use asbestos-containing products, or live or work in buildings with deteriorating asbestos insulation or that have undergone poorly performed asbestos removal.[1]

READ MORE...

People may also be exposed during home renovations if asbestos containing materials are disturbed. Asbestos was used in over 3,000 different building materials used from the 1950s to 1990s such as stucco, flooring, roof shingles, and insulation.[2,3] Family members of asbestos workers may also be exposed through contaminated work clothing.[4] CAREX Canada estimates that asbestos levels in indoor and outdoor air may result in increased risks of cancer at a population level (very low data quality).

Vermiculite insulation produced between the 1920s and 1990s and used in homes may contain amphibole asbestos and could be an exposure hazard if disturbed.[5] Vermiculite products marketed for garden use may also contain asbestos. An EPA study in the Seattle area in 2000 found 5 of 16 purchased products were contaminated with asbestos.[6]

Although contaminated air is the most important route of exposure in the general population, people may also be exposed by ingesting drinking water in areas where asbestos occurs (either naturally or from human activities). There is a great deal of debate on the carcinogenic role (if any) of exposure to asbestos via drinking water. In general, there is no consistent evidence to support this hypothesis.[7,8] CAREX Canada estimates that exposure to asbestos via drinking water or food and beverages is negligible.

Asbestos is geologically related to talc, a substance that may be used in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, and as a food additive. Talc from some mine deposits can be contaminated with asbestos, especially anthophyllite and tremolite.[7] When used as a food additive, talc must be asbestos free, as per the Food and Drug Regulations.[9] The Prohibition of Asbestos and Products Containing Asbestos Regulations prohibits asbestos above trace levels in consumer products, including cosmetics.[10] However, the responsibility of testing lies with the manufacturers.

Searches of Environment Canada’s National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) and the US Household Products Database yielded the following results on current potential for exposure to asbestos in Canada:

NPRI and US Household Products Database

| NPRI 2017[11] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Substance name: ‘Asbestos (friable form)’ | ||

| Category | Quantity | Industry |

| Released into Environment | None | Waste treatment and disposal, Remediation and waste management, petroleum and coal product manufacturing pesticide, fertilizer and other agricultural chemical manufacturing, oil and gas extraction (50 facilities) |

| Disposed of | 24,126 t | |

| Sent to off-site recycling | 28 t | |

t = tonne

| US Household Products 2018[12] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Search Term | Quantity | Product Type |

| ‘chrysotile asbestos’ | 5 | Roofing sealant cements |

| ‘anthophyllite asbestos’ | 4 | Paint primer |

Cancer Risk Estimates

Potential lifetime excess cancer risk (LECR) is an indicator of Canadians’ exposure to known or suspected carcinogens in the environment. When potential LECR is more than 1 per million in a single pathway, a more detailed risk assessment may be useful for confirming the need to reduce individual exposure. If measured levels of asbestos in relevant exposure pathways (outdoor air and indoor air) decrease, the risk will also decrease.

Potential LECR due to exposure to asbestos is calculated by multiplying lifetime hourly concentration by a unit risk factor. More than one cancer potency factor may be available, because agencies interpret the underlying health studies differently, or use a more precautionary approach. Our results use unit risk factors from Health Canada, the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), and/or the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA).

The calculated lifetime hourly concentrations and LECR results for asbestos are provided in the tables below. For more information on supporting data and sources, click on the Methods and Data tab below.

Calculated Lifetime Hourly Concentrations

Lifetime Excess Cancer Risk (per million people)

*LECR based on average intake x cancer potency factor from each agency

Compare substances: Canadian Potential Lifetime Excess Cancer Risk, 2011

The data in this table are based on average intake and Health Canada’s cancer potency factor, assuming no change in measured levels. When Health Canada values are not available, United States Environmental Protection Agency values are used.

Click the second tab to view LECR data.

**Exposure not applicable: For indicated pathways, substance not present, not carcinogenic, or exposure is negligible

**Gap in data: No cancer potency factor or unit risk factor, or no data available

IARC Group 1 = Carcinogenic to humans, IARC Group 2A = Probably carcinogenic to humans, IARC Group 2B = Possibly carcinogenic to humans

NOTE: Chromium (hexavalent) estimates assume that 5% of total chromium measured in outdoor air is hexavalent and 8% total chromium measured in indoor dust is hexavalent.

Potential LECR assumes exposure occurs at the same level, 24 hours per day, for 70 years. This is rarely true for any single individual, but using a standard set of assumptions allows us to provide a relative ranking for known and suspected carcinogens across different exposure routes. While ongoing research continually provides new evidence about cancer potency and whether there is a safe threshold of exposure, our approach assumes there are no safe exposure levels.

Mapping

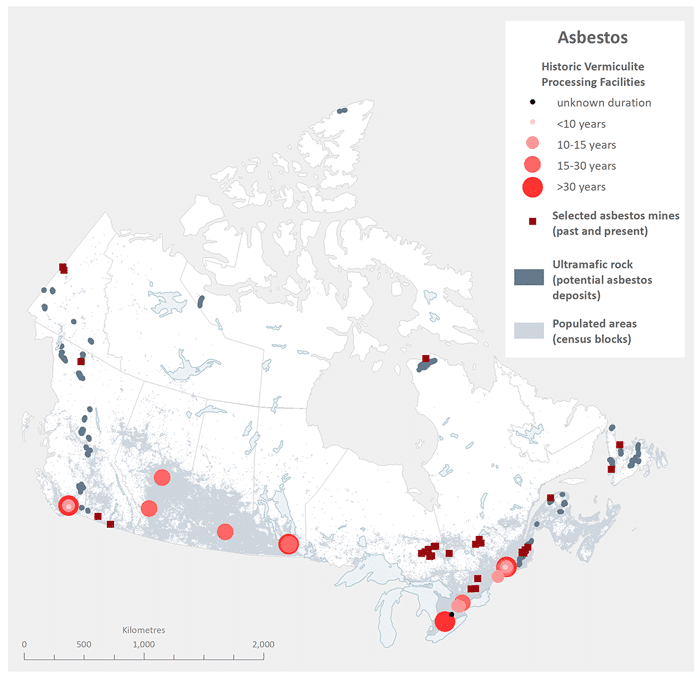

Exposure to asbestos may have occurred historically in communities close to asbestos mines, and may still be occurring when waste piles containing asbestos are present.[13,14,15] In the past, people who lived near manufacturing facilities producing insulation with asbestos-contaminated vermiculite from Libby, Montana may have been exposed;[16,17,18] and recent studies also suggest that exposure might occur when naturally occurring asbestos deposits are disturbed.[19] Vermiculite produced by the Libby Mine in Montana from the 1920s-1990 and sold as Zonolite® Attic Insulation may contain amphibole asbestos,[20] and potential exposures may occur in homes where Zonolite® insulation is disturbed.

Selected Asbestos Mines, Historic Vermiculite Processing Facilities and Potential Naturally Occurring Asbestos Deposits

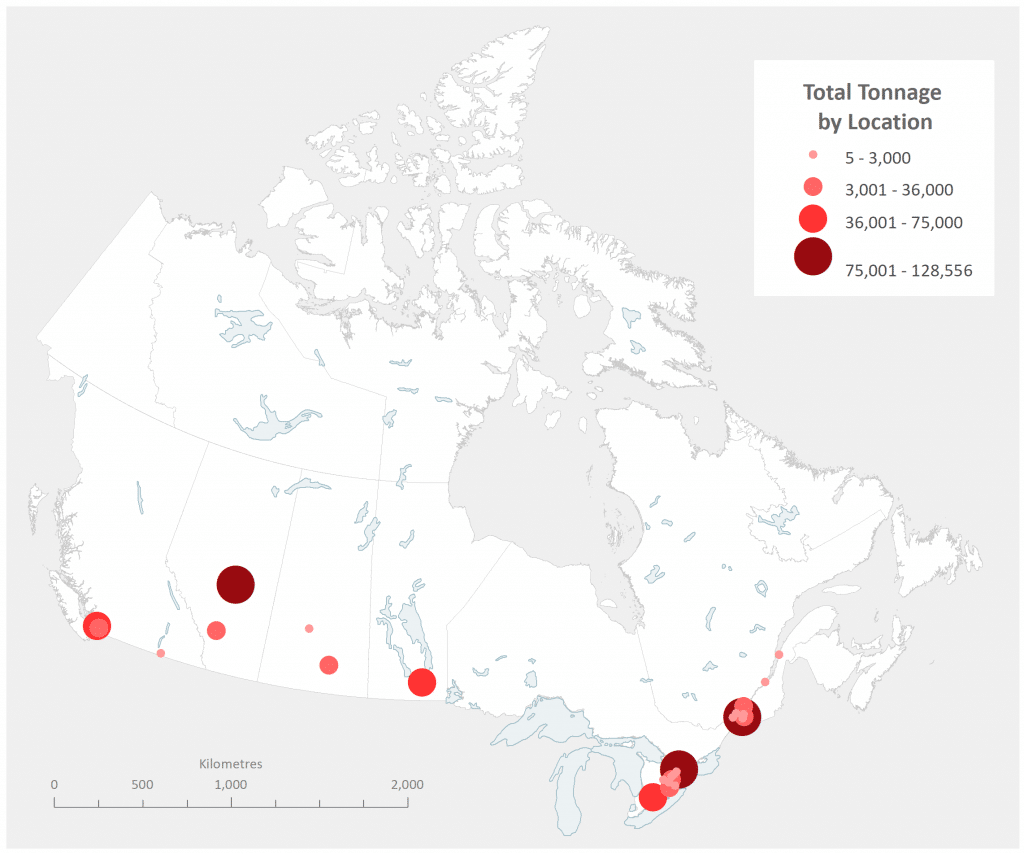

Canadian Distribution of Libby Ore Shipments from 1964-1990 (in tons)[21]

Asbestos Production

Exposure to asbestos may have occurred historically in communities close to asbestos mines, and may still be occurring when waste piles containing asbestos are present.[12,13,14] In the past, people who lived near manufacturing facilities producing insulation with asbestos-contaminated vermiculite from Libby, Montana may have been exposed;[15,16,17] and recent studies also suggest that exposure might occur when naturally occurring asbestos deposits are disturbed.[18] Vermiculite produced by the Libby Mine in Montana from the 1920s-1990 and sold as Zonolite® Attic Insulation may contain amphibole asbestos,[19] and potential exposures may occur in homes where Zonolite® insulation is disturbed.

The last two operating asbestos mines in Canada – both in Quebec – closed down in 2012.

Annual Asbestos Production in Canada: 1886 to 2011[22,23,24]

*Data not available in 1987 for QC, BC, NL

Known asbestos producers and mine locations in Canada 1943 to 2006[23]

Vermiculite Processing

In 1916, the world’s largest deposit of vermiculite was discovered near Libby, Montana. The vermiculite was mined primarily for use as an insulating material. Crude (or raw) vermiculite was shipped from the mine to processing plants across the US and in Canada, where it was exfoliated using high temperatures causing it to expand significantly. In 1935, a report from the US Bureau of Mines noted the presence of a series of amphibole asbestos dikes, up to 10 feet thick intersecting the vermiculite deposit. Over the entire operating life of the Libby mine (1921 to 1992), the vermiculite extracted and shipped for processing was contaminated with this particularly carcinogenic form of asbestos.[23,25]

Vermiculite was mined and processed commercially in Canada only for a very short time (1956, 1957, and 1966) and in very small quantities at a location near Stanleyville, Ontario. All other vermiculite processed in Canada was imported from the United States, predominantly from Libby mine, or from South Africa (presumed to be uncontaminated).

Available data sources regarding Canadian imports of vermiculite include: 1) general information on all imports to Canada from South Africa or the United States reported in mineral yearbooks from the United States Geological Survey and Natural Resources Canada, and (2) invoices of vermiculite shipments from the Libby Montana Mine to companies in Canada from the United States Environmental Protection Agency. See more information about each data source below.

Canadian Imports Reported in Mineral Yearbooks (CAN & US)

The graph below shows tonnes of crude vermiculite imported from the US and South Africa for years with available data. USGS Bureau of Mines reports note that vermiculite from the Libby mine was being exported to Canada for processing as early as 1935 (Winnipeg, MB and Paris, ON).[25] See the map for more information on processing sites in Canada.

Annual Imports of Crude Vermiculite: 1963 to 1992[23,25]

Libby Mine Invoices

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has compiled a database documenting W.R. Grace invoices for shipments from the Libby Mine from 1964 to 1990.[26] The database includes company name, shipping destination, and total tonnage shipped. The EPA database may not include every shipment made during this time.

Although the number of sites and amount of ore received may be understated by invoices in the database, the EPA has investigated sites in the United States thought to have received ore to determine if remediation activities are necessary. Investigations have not been carried out for Canadian shipment locations.

The following table reports W.R. Grace invoices for shipments of vermiculite from Libby Mine to Canadian locations from the EPA database. No information is available on the end uses of vermiculite shipped to reported Canadian locations; some may have been shipped directly to facilities engaged in vermiculite processing, while others may have been subsequently transported to other locations for other intended purposes.

At least 8,252 shipments of vermiculite were made from Libby, MT to locations in Canada; the majority of shipments and total tons to Ontario, Quebec, and Alberta. See the table below and map for more information on shipment locations in Canada.

Total Number of Shipments from Libby, MT to Canada: 1964-1990

Invoices from Libby, MT to Canadian Locations: 1964-1990

Home Insulation

The number of homes in Canada insulated using Zonolite® is unknown; however, it is estimated to be present in 3% of low-rise houses across Canada, or 242,000 homes in residential neighbourhoods, including First Nation Housing, and on Canadian military bases.[27]

From 1977-1986 the Canadian Home Insulation Program (CHIP) provided grants to homeowners for improving the energy efficiency of their homes. During this time 2,592,392 grants were issued for approximately 150 different types and brands of insulation products, including Zonolite® vermiculite insulation.[28] The actual number of homes which insulated using Zonolite® under the program is unknown, as CHIP was instituted prior to digital record-keeping. Existing paper records may contain information on a residence-by-residence basis on the products purchased under the grant to upgrade home insulation. These paper records may indicate potential exposure in homes that were insulated with Zonolite®, but would not reflect those that have since been remediated.

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) has reviewed their records to attempt to identify where vermiculite insulation containing asbestos may have been used in the construction of houses on reserves.[29] Of houses built between 1960-1990, INAC found 597 references to houses that may have been built using Zonolite® Loose-Fill Vermiculite Insulation in the provinces of Saskatchewan (276), Manitoba (234), British Columbia (28), Quebec (28), and Alberta (5). An additional 6 references in the Yukon identified the use of vermiculite in general, but not specifically the Zonolite® brand. No records were available for the Northwest Territories of Nunavut, as housing is under the jurisdiction of Territorial Governments.

The Department of National Defence has assessed their complete housing portfolio.[27]

Health Canada has posted extensive information about vermiculite insulation that may contain asbestos on their website.[20]

Methods and Data

Our Environmental Approach page outlines the general approach used to calculate lifetime excess cancer risk estimates and includes documentation on our mapping methods. The documents below outline (1) the specific methods for asbestos lifetime excess cancer risk estimate calculations and (2) the data sources and data quality for asbestos estimates.

(1) LECR Methods – Asbestos [PDF]

(2) Supplemental data – Asbestos [PDF]

Sources

Subscribe to our newsletters

The CAREX Canada team offers two regular newsletters: the biannual e-Bulletin summarizing information on upcoming webinars, new publications, and updates to estimates and tools; and the monthly Carcinogens in the News, a digest of media articles, government reports, and academic literature related to the carcinogens we’ve classified as important for surveillance in Canada. Sign up for one or both of these newsletters below.

CAREX Canada

School of Population and Public Health

University of British Columbia

Vancouver Campus

370A - 2206 East Mall

Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3

CANADA

As a national organization, our work extends across borders into many Indigenous lands throughout Canada. We gratefully acknowledge that our host institution, the University of British Columbia Point Grey campus, is located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people.